This summer I was able to spend several weeks documenting how various First Nations around Vancouver Island, Canada are dealing with industrial scale fish farming operations in their territory. Earth Island Journal and Civil Eats co-published the story this winter. Find the story online at the links below. Photos from the story below, including unpublished outtakes. Images for this story came from this reporting trip, the Tribal Canoe Journey I had the chance to join a few years ago through the region, and other past work in the area.

Grateful to the numerous First Nations’ members that shared their stories and perspectives on an issue of critical material and cultural importance to them. This reporting was possible thanks to a grant from the Society for Environmental Journalists as well as on the ground in-kind support and research assistance from Ocean Outfitters in Tofino, BC, which offers carbon neutral tours in Clayoquot Sound. Nyn Tomkins helped with photography and logistics in the field. As always great to work with the editorial teams at Earth Island Journal and Civil Eats!

A chinook salmon ready to be prepared for a feast by the Wuikinuxv First Nation.

Two members of the Wuikinuxv First Nation prepare wild salmon to feed to guests to their territory duirng the annual Tribal Canoe Journey which brings together First Nations from up and down the Pacific Northwest. Each night the local First Nation where the canoe journiers spend the night prepares a feast to serve to their guests.

Fillets of wild salmon are cooked next to an open fire in the traditional manner using split western red cedar wood to secure the fish by the fire. Wuikinuxv First Nation territory.

A male and female Sockeye salmon preparing to spawn in a small tributary of the Fraser River in the unceded traditional territory of the Secwepemc First Nation.

A chum salmon decomposes in a shallow coastal stream after spawning. Heiltsuk First Nation unceded traditional territory.

Old growth western red cedar rainforest on Flores Island. Ahousaht First Nation territory

Ahousaht member Lenny John is an outspoken critic of his nation's approach to fish farms and has engaged in numerous protests and direct actions against the farms. “The hereditary chiefs and Chief of Council work for Cermaq. They protect the company. They are getting rich off of it but Ahousaht is poor,” says Len John, an Ahousaht member who runs a small boat charter and water taxi company. “We, the people, don’t see that money. We have homeless people, elders with homes that are gutted, with no running water.” Ahousaht hereditary chief Richard George refutes these claims.

A Cermaq fish farm in Ahousaht First Nation's tradtional territory at Saranac Island in Clayoqout Sound. The boat docked by the farm is set up to pressure wash sea lice off of the Atlantic salmon in the farm.

Cermaq fish farm anchored to Saranac Island in the Ahousaht First Nation's territory.

Cermaq's fish processing plant in Tofino British Columbia. Tla-o-qui aht territory

The mouth of the Moyeha River were it empties into Clayoqout Sound. Almost the entire river's watershed is protected in a provincial park but the salmon runs in the river have crashed. To access the open ocean, young salmon leaving the river must pass multiple fish farms owned by Cermaq.

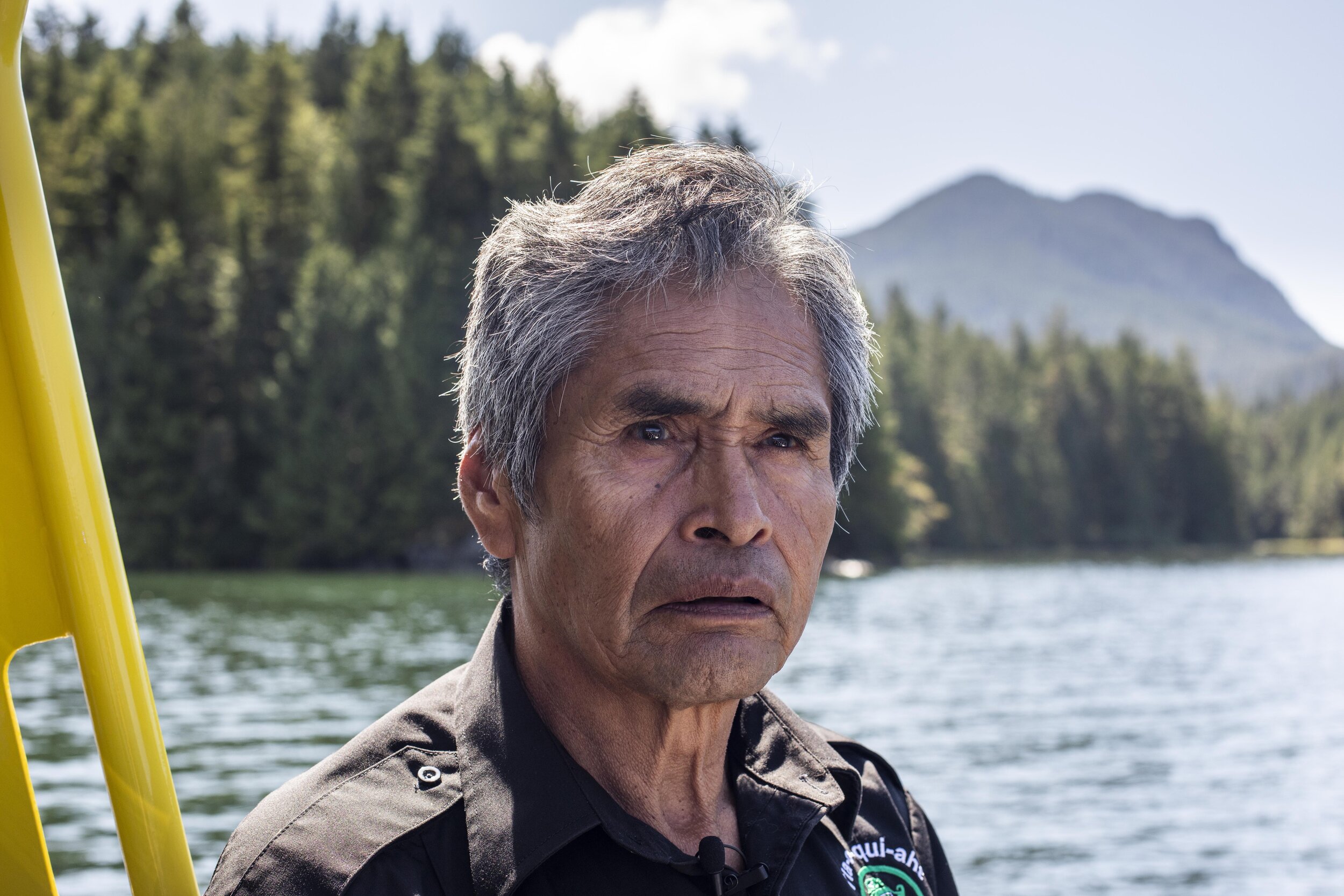

Joe Martin, master carver, Tribal Parks Guardian, elected member of council for Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation blames fish farms for the continued decline of wild salmon in his peoples territory. “The rivers here aren’t being fished,” says Martin, “but still salmon runs are still declining.” Martin believes this is “because the wild juvenile salmon are being infected with sea lice and viruses as they swim past the fish farms.” Martin also notes that he believes “many of the juvenile salmon are attracted to the food at the fish farms as it’s the same food as the salmon enhancement program” where the TFN raises fish for release into the wild.

A collection of sea lice on an adult Chinook salmon caught in the open ocean. On an adult fish these sea lice are harmless. This many lice on a juvenile salmon could be fatal. Tla-o-qui-aht territory

Concerns about fish farms are not limited to First Nations members in the region. Ryan Millar, who captains a whale watching boat, and fishes recreationally fillets a chinook he caught in Clayoquot Sound. "At first glance I see a great alternative to depleating wild fish but after 16 years here on the ocast I would say there is a lot of negative science refuting the benifit. They are an eye-sore for Tofino--if they were going to be anywhere in BC they shouldn't be here"

A totem pole in the front yard of a house in Alert Bay, home of the Namgis First Nation.

Commercial fishing boats, many of them in disrepair in Alert Bay, BC, speaks to the decline of fishing opportunities in the region. Many Namgis members were commercial fishermen before the local fisheries were closed due to declining stocks of fish.

“Twenty years ago, I would expect that I would easily get 150 sockeye,” says Ho’miska̱nis, aka Don Svanvik, a hereditary chief and current elected chief of council of the ‘Na̱mg̱is First Nation. “I would can a whole bunch and freeze about 70 of them, 40 of them to be smoked when it cools off, the rest to eat throughout the year. Last year I caught four.” Svanvick helped negotiate the terms of the agreement with Canada, and BC which has lead to the removal of fish farms from his peoples traditional territory.

Chief Earnest Alfred, K̓wak̓waba̱'las, elected council member of the 'Na̱mg̱is First Nation traditional leader of the Ławit̓sis First Nation, with his family at the naming ceremony for his grand daughter in Alert Bay. Alfred was instrumental in the occupation of a fish farm in their territory which has helped bring an end to them in the Broughton. “For our people, salmon is not a menu choice. It’s within our DNA. We are the fish. We are the salmon people.”

Alexandra Morton at her home on Malcolm Island in the territory of the Namgis First Nation. Morton has been studying the impacts of fish farms on wild salmon for decades, with a focus on the impacts of sea lice on juvenile salmon. With the local commercial fishing and guided sports fishery in her area gone she quipped, “the only thing eating wild salmon out here is sea lice.” She has written a book on her work, Not on My Watch. I had the chance to interview and photograph Morton at her home in Namgis traditional territory

Alexandra Morton inspects a juvenile salmon for sea lice at her home on Malcolm Island in the territory of the Namgis First Nation