Use Tracking Skills To Find & Photograph Elusive Wildlife: An Interview With David Moskowitz

This summer, my colleague Jaymie Hiembuch, asked me to do an interview with her for her great podcast: Impact: The Conservation Photography Podcast. I was delighted to join her for a conversation about something I don’t often talk about specifically—how to apply wildlife tracking skills for wildlife photography. Jaymie is a delightful interviewer and extremely talented photographer and storyteller.

OR7 Expedition Revisited

The Oregon Department of Wildlife recently announced that wolf OR7 has likely passed away over the winter. The news inspired me to go back and reflect on the expedition that I joined to retrace the steps of this animals amazing 1200 mile dispersal which took him from northeastern Oregon down into California and back into southwest Oregon.

In the spring of 2014, a team of 5 of us, supported by a dedicated logistics member, set out for over a month on foot and bicycle to retrace the route of OR7 in order to see the world that this 21st century wolf encountered. It had been nearly a century since wolves where last known to be present in most of the landscapes he traveled through and a lot has changed in 100 years.

Here are some photos from the expedition. Learn more about OR7, his journey and ours, at our expedition website: or7expedition.org where you can also stream the documentary we produced about the expedition and what we learned about human-wildlife co-existance in the modern world along the way.

Fishers return to the North Cascades

A partnership between tribes, multiple government agencies in the United States and Canada, and Conservation Northwest is bringing fishers back to the North Cascades. Fisher were extirpated from the region by fur trapping and poisoning campaigns in the 1900’s. On October 24, 2019, 8 fishers were released on the traditional territory of the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe on the west slope of the North Cascades close to the town of Darrington, Washington.

Scent marking black bears

While camera trapping this summer for wolverines I got an awesome series of photos of black bears communicating with each other through scent marking on a tree in the North Cascades of Washington (Nlaka'pamux First Nation Traditional Territory).

A black bear smells a marking tree to learn about other bears that have visited the tree.

When bears mark trees they focus on two heights on tree, about bum height (for the bears) and should height for a standing bear. Here you can see the same bear inspecting the scent left behind by a previous bear.

And here’s the bear the first one was smelling rubbing its head against the tree. This black bear has a much lighter brown coat of fur.

The same brown colored black bear rubbing its shoulders and back on the tree.

Fishers Return to the North Cascades

Southern Selkirks Herd Declines But Efforts to Save Caribou and The Rainforest Continue

"Functional Extinction" But Most Definitely NOT Game Over.

Many of you may have caught wind of the recent news about the continued decline of the Southern Selkirks herd, the last transboundary herd of Mountain Caribou. Their story was featured in articles in the New York Times in the United States and The National Post in Canada, both featuring an image from this project of one of the last animals from this herd.

While these two stories had catchy headlines, they generally missed that, for the tribes and conservation groups working on this topic, it is most certainly not "game over". See this article in the Northwest Sportsman Magazine which includes an interview with Kalispell Tribal biologist Bart George, this press release put out by project partner Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, and this blogpost from Conservation Northwest.

This news marks the start of a pivotal moment for the conservation of the Caribou Rainforest. Indigenous peoples legal rights to access these traditional animals are not just rolling over with this news. Now is a moment to continue to stay engaged in this topic in support of their legal rights and our society's moral obligations.

With the potential demise of this and a number of other herds, habitat protected for them could go back on the chopping block. This ecosystem, for which the caribou is emblematic, will need protection with or without caribou. Along with our continued support of caribou specific conservation efforts, we must also seize this moment to grow our message to focus consistently on the Ecosystem rather then just the species.

To that end, I am excited that the photography book which is the culmination of much of the work of this project will be out this fall. Our film, Last Stand: The Vanishing Caribou Rainforest, is an expose of the destruction ongoing in this ecosystem. The Caribou Rainforest: From Heartbreak to Hope, published by Braided River, is our attempt to celebrate and highlight this amazing and overlooked ecosystem, one of the most unique forest ecosystems on planet Earth. With or without caribou, The Caribou Rainforest is a place worth protecting. For all the other creatures that call this place home, for all the people whose lives and cultures are tied to it, and for everyone who depends on a stable climate and cares about what future generations will be inheriting from us.

This fall, along with the release of the book and a renewed schedule of slideshows and film screenings we will be releasing the film for online viewing in order to get these two messages out as far and wide as possible.

We continue to be grateful for all the support we have received up to this point and continue to look for funds and opportunities to get our material and message out as far and wide as possible. Braided River is currently fundraising to support outreach activities aligned with the release of the book.

More work ahead. We carry one.

Cascades Wolverine Project

I am excited to be starting a new collaboration this winter right in my own backyard here in the North Cascades. Cascades Wolverine Project is a grassroots effort to boost winter wolverine monitoring in the North Cascades, capture engaging images of this elusive mountain carnivore, and leverage the skills of winter backcountry recreationists as wildlife observers and alpine stewards. Learn more about the project on our website cascadeswolverineproject.org, or follow along on instagram at @cascades_gulogulo We currently have 6 camera trap installations set up on the eastside of the North Cascades for the winter and have completed our first camera check of the season. No wolverines yet but we did get some fun photos of other North Cascades critters! Along with running camera monitoring stations we will be working on developing more opportunities for backcountry skiers to get more involved in wolverine conservation in the North Cascades!

Project leader Steph Williams having absolutely NO FUN during our field work. Follow Steph on instagram at @stephwilliams9010.

Field Notes: Winter in the Monashee Mountains

Photos and text by David Moskowitz. Expedition partners: Steph Williams and Forest McBrian.

A Fruitless Search For Caribou

We go to the mountains searching for answers. We go to the forests looking for clues. We watch the clouds roll across the peaks, keen to see what the universe will deliver on the wind. We scan the snow for the tracks of elusive creatures of the wild wonder about their lives when we find them and their absence when we don’t.

Back home, developing images of stark landscapes Carved by forces beyond our comprehension Turned to black and white and every shade of grey in between. Their is a haunting beauty in precarious landscapes Unsettled times What’s missing from our maps? What’s hidden in the clouds? When will these mountains come tumbling down?

Mountain Caribou Initiative: Camera Trapping for Carnivores

Text and photos by David Moskowitz Caribou are not the only animal tough to track down in the Caribou Rainforest ecosystem. As part of our efforts to tell the story of all of the creatures that call these mountains home, I have been setting camera traps this winter in collaboration with Swan Valley Connections in northwestern Montana and the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in the panhandle of Idaho this winter to capture images of some of the rare and elusive carnivores that depend on this wild landscape. Here are a few images from this winter field work and some out-takes of images from the camera traps.

Anything unusual about this snowmobile packing job? Researchers in Idaho and Montana are using beaver carcasses or deer legs as attractants to lure rare carnivores like Canada lynx and wolverines to bait stations set up with hair snagging devises to collect genetic samples from animals without ever having to see or handle the animals. I’ve been hitching a ride out into the field with researchers and setting up my camera traps adjacent to their bait stations.

Cody Dems (left) and Adam Lieberg set a bait station in the Mission Mountains of Montana.

Cody inspecting the fresh trail of a wolverine in Montana.

A Canada lynx enjoys some sunshine in a photo from one of my camera traps in Montana. Got many photos of this fellow in this beautiful subalpine forest. Its been many decades since caribou roamed these forests but lynx continue to call these mountains home.

A photo bombing snowshoe hare set up in front of another camera in the Selkirk Mountains in Idaho.

An American marten takes in a snowy night at the same camera trap as the snowshoe hare above.

Learn more about the Mountain Caribou Initiative here. Stay tuned for the trailer for our forthcoming film which should be out this spring. For updates on the film and other material forthcoming from the project, sign up for quarterly emails on the About page of my website.

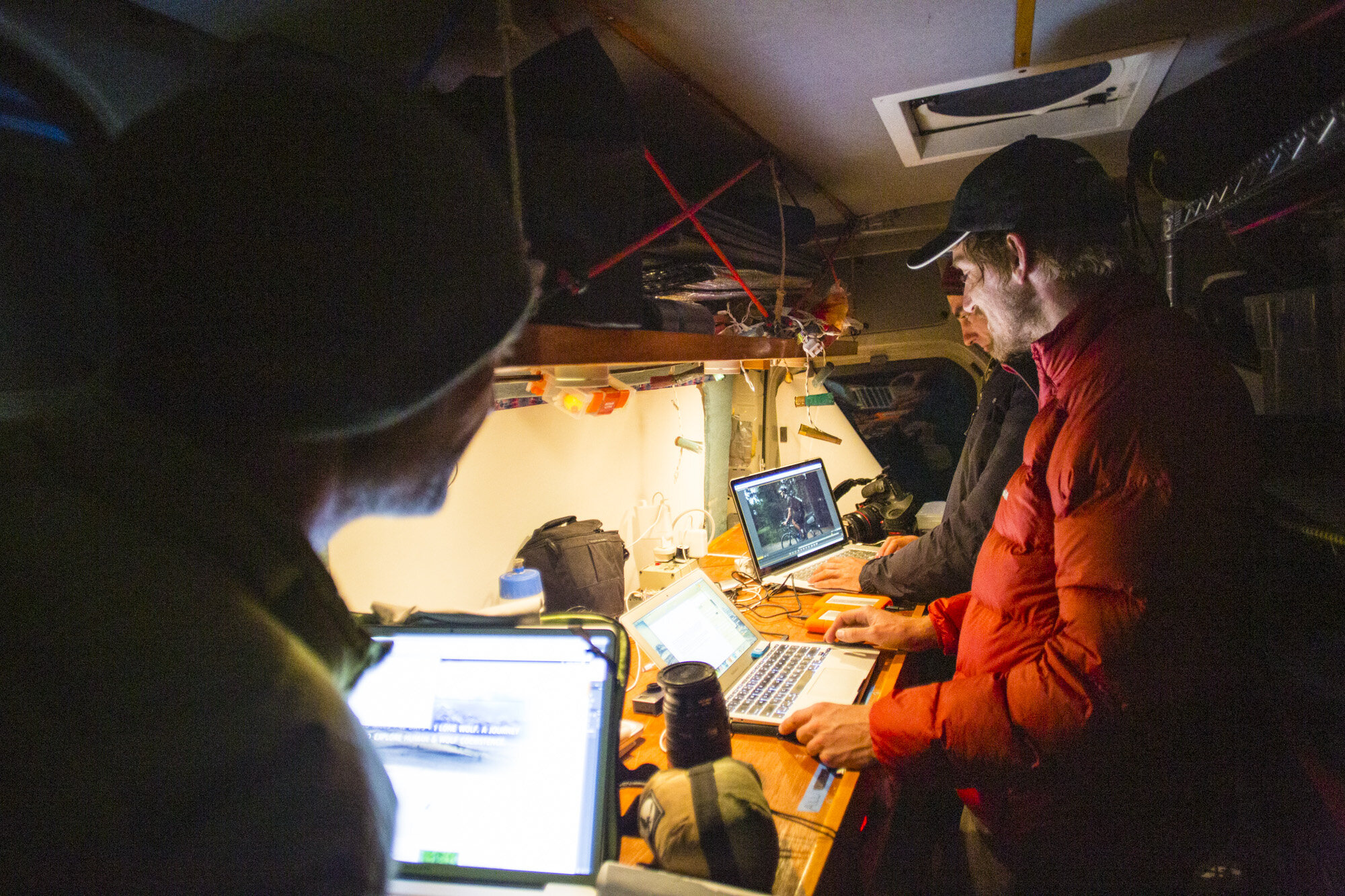

Wolf OR7 Expedition Documentary: Now Available Free Online

Watch the full Wolf OR7 Expedition Documentary.

People of the Caribou Rainforest

People of the Caribou Rainforest

Text and photography by David Moskowitz

Over the course of our team's explorations of the Caribou Rainforest we have had the chance to meet many folks who live, work, and play in this unique region of the world. We have talked with and learned from First Nations people - whose families have been on this land for millennia - and vacationers from Europe here for just a week of vacation. We've talked with snowmobilers and backcountry skiers, loggers and environmental activists, foresters and wildlife biologists.

The variety of voices we have heard has given us a wide variety of perspectives on the ecology, economy, history and culture of the region. Here are just a few of the people who have shared some of their thoughts with us over the past year as we seek to collect stories and perspectives from people across the region.

Revelstoke Community Forest Corperation forester Kevin Bollefer and his dog gave us a tour of some of the experimental harvest methods they have been trying in order to minimize the impact of forestry activity on caribou.

Brian Pate, biologist for Wildlife Infometrics uses a spotting scope to search for caribou and other wildlife in the Hart Range.

Chief Roland Wilson of the West Moberly First Nation spoke with us about his people’s connection with their traditional homeland and the current state of caribou conservation in that region.

Paul Sarafinchan has been logging for three decades in the interior of British Columbia.

Kate Devine, of Revelstoke BC, spends her summers cruising timber (evaluating stands of trees for their lumber value) and her winters working as a backcountry ski guide.

Harley Poitras currently works as a log truck driver and informed us that “You can’t call yourself a log truck driver until you’ve rolled a truck at least once.”

David Walker allowed us to follow him around for a morning of work felling trees in the northern Selkirk Mountains.

Ryan “Dunny” Dunford kicked up some powder for us on his mountain sled on Boulder Mountain.

Doug Heard, a legend in the world of Canadian caribou biology, shared stories and his current interests in caribou conservation from his home outside of Prince George.

We interviewed Kootenai Tribal Chairman Gary Aitken Jr. along with biologists Scott Soults and Norm Merz at the tribal headquarters outside of Bonners Ferry, Idaho. The Kootenai tribe has taken on developing an updated management plan for mountain caribou on the USA side of their range for the USFWS. Gary noted to us that the Kootenai have a “covenant with the creator and a sacred obligation to care for the land.” Their goal was, rather than look at things “species by species”, to “take a ridgetop approach” in looking at how to “bring the ecosystem back to more natural levels.”

Gilbert Desrosiers is president of the Beaver Mountain snowmobile club in the West Kootenay mountains and has worked with the province of BC and the Nature Conservancy of Canada to ensure responsible riding in the Kootenays.

Three buddies from the eastern United States paused to chat with us at Kootenay Pass in the Southern Selkirks during their week-long backcountry ski vacation to the region.

Outward Bound Instructor Judith Roberston of Nelson British Columbia on a backcountry ski tour in the southern Selkirk mountains.

Harley Davis and Garret Napoleon of the Saulteau First Nation at the Klinze-sa Maternal pen where they help monitor captive caribou cows and calves.

Erik Leslie (left), the forester for the Harrop-Proctor Community Forest, and two board members look over a map of the region they are responsible for managing.

Gordie Hale takes a break from his work moving logs on a logging operation in the southern Selkirk Mountains.

Naomi Owens, Treaty Manager for the Saulteau First Nation discussed her people’s involvement in protecting caribou and other resources on their traditional territory.

Helicopter pilot Timothy Seabrook removing the door to his aircraft in the Hart Range.

Revelstoke Snowmobile Club president Daniel Kellie along with two club members, lean on the club’s new groomer close to the very popular Boulder Mountain trailhead, also the location of a dwindling number of mountain caribou.

Ecologist Greg Utzig of Nelson British Columbia was part of the negotiations to create the 2007 Mountain Caribou Recovery Plan which currently steers conservation efforts of caribou in British Columbia.

Some of wildlife Biologist Rob Serroya’s research includes investigations into the relationship between moose and wolf populations and their relationship to caribou population dynamics.

Along with collecting the stories of the people of this region, our team has been busy creating stories of our own out in the field. While we work to help create understanding across many groups of people and on a variety of geographic scales, the people, places, and wild animals of this region have been shaping who we are as well.

Marcus Reynerson in a blind we constructed in the Monashee Mountains in July of 2015.

Kim Shelton seeks shelter from the rain this summer in the southern Selkirk Mountains close to the Washington-BC border.

Colin Arisman skinning up through treeline in the Columbia Mountains in February 2016 on a multiday backcountry tour in the winter range for the North Columbia herd.

David Moskowitz inspects a recent clearcut in the Upper Seymour River on the west slope of the Monashee Mountains. Photo by Marcus Reynerson.

Close to Caribou

Text by Kim Shelton. Photos by David MoskowitzDay two in the 2016 summer expedition of the Mountain Caribou Initiative: our mission is to set up camera traps in core home range of the Southern Selkirk mountain caribou herd a few miles from Kootenay pass, just north of the U.S. border. My secondary mission is to keep up with David Moskowitz, scrambling up and down mountains while carrying a pack loaded down with camera trap gear. I'm constantly amazed at the terrain that these caribou seem unfazed by, and that we must traverse if we want to find sign of them. It is absolutely rugged country and stunningly beautiful.

Dave also seems to be unfazed by the terrain, scaling peaks and traversing talus fields at a doggedly consistent and efficient pace – a result of having made a living in the outdoors for two decades. His goals at first seem completely unreasonable to me. The day is long: 11 hours of bushwhacking, with intermittent pauses to investigate tracks and set up camera traps – and I keep up mostly because I’m too stubborn not to.

Dave also seems to be unfazed by the terrain, scaling peaks and traversing talus fields at a doggedly consistent and efficient pace - a result of having made a living in the outdoors for two decades. His goals at first seem completely unreasonable to me. The day is long: 11 hours of bushwhacking, with intermittent pauses to investigate tracks and set up camera traps - and I keep up mostly because I'm too stubborn not to.

The tracks of a wolf in a high mountain meadow in the Selkirk mountains.

At our first summit of the day, on a ridgeline south of Canadian Highway 3, we gaze down at a wetland meadow system far below. Somewhere down there we hope to find sign of one of the twelve animals in the South Selkirk herd. I'm scanning the landscape with my binoculars every chance I get as we descend the steep hillside, at times lowering ourselves down hand over hand using spruce branches or handfuls of pacific rhododendron, trusting the hardy mountain plants will hold our weight.

I "glass" the hills again near the bottom of our descent, having learned last year to always look twice after I scanned right over a camouflaged bedded down moose. I slowly check every suspicious looking rock, stump, and waving branch.

A single white tailed deer feeds across the valley from us. According to the Wildlife Management Institute, white tailed deer were historically rare in this area but now comprise almost three quarters of the deer population in the Selkirk Mountains. These deer, along with moose and elk, are considered “primary prey” for wolves and mountain lions, predators that weren’t so much of a threat to mountain caribou years ago, but with the fracturing of the inland temperate rainforest by clearcuts, roads and powerlines, “primary prey” moved in, followed by their predators.

One of the main defense systems of mountain caribou is evasion of predators; carried by their massive hooves they retreat to snow covered peaks in winter and spongy marshlands in the summer, away from where other hoofed animals and their predators typically roam. Naturally they become prey at times, but a large herd can replenish a loss. At twelve animals and with cows taking three years to birth their first calf, and then only one per year after that, replenishment is slow. Compared to a white tailed deer who can birth up to three fawns her first year, the Southern Selkirk mountain caribou herd is fragile to say the least.

In the marshy valley bottom mosquitoes descend upon us as we split up to scan the area for sign. I’ve given up trying to keep my feet dry as I squish across the meadow, searching for game trails, scat, tracks, rubs, browse sign. I did not expect to see bones. White and clean, I can immediately tell they are leg bones of an ungulate - a long legged, gracefully hoofed animal. As a tracker, finding the remains of an animal always gets me excited. I crouch by the few bones and play out all the possibilities of what may have happened here. Knowing that the rest of the carcass must be near by, I stand and move intuitively, loving the sense of calmness that takes over my mind and body when following animal sign. I walk right to the carcass; a large spread of fur and bones lies peacefully amidst a thicket of downed trees and branches on the edge of the marsh.

Now my mind turns on, investigating. Lots of hollow fur, very light colored, the leg bones seem huge, too big for a deer...elk? Moose? The color of the fur is not right, elk are more red but I can’t remember how much white moose have on them. The leg bones are cracked, wolves and wolverines often crack long bones like this, bears do as well occasionally. Did they kill it or did they scavenge?

I take a stick and push the fur around, trying to find more evidence. Somewhere in my mind the debate of whether I want this to be a caribou or not is taking place. The head is nowhere to be found, but I find a single dewclaw. It is very curved. My heart beats faster and sinks at the same time. But I can’t tell yet - the kill site is old and the only way to tell for sure is to take the time and research all the possibilities. So Dave takes pictures, and we bring this mystery out of the mountains with us.

Norm Merz, a Wildlife Biologist for the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, met with us the next day and confirmed that yes the carcass was that of a mountain caribou. He had been in there just days before and was awed that we happened upon the exact same place. He also confirmed our suspicions that it was fed on by wolves and also by bears, but the exact cause of death is unknown. Biologists from the province of British Colombia had taken the head to investigate the sex of the animal. As both males and females grow antlers, the presence of single tine “spike” antlers on this carcass indicated that the animal was either an adult cow or young bull. Norm expressed his relief in seeing that the teeth were sharp - this animal hadn’t spent years grinding lichens - it was a young bull. Norm noted wryly that any loss from this herd is problematic for their ultimate survival, but females, on whom the future growth of this herd depends, are especially important for herd survival.

Opposing feelings of celebration and tragedy once again battle inside of us. This project has become such a contradictory experience. Constantly we search for success - but success is finding a dead bull caribou instead of a dead cow, or finding their tracks coming out of a clear cut. Failure is having spent all day in beautiful country - prime caribou habitat in the largest remaining inland temperate rainforest in the world - and finding absolutely no sign that caribou even exist.

I have never seen a mountain caribou. I have bushwhacked for miles, seen their tracks and their scat. I have stared at maps, seen photos, heard stories and even dreamt of them. But the closest I’ve ever been to a mountain caribou was touching the bones of a young bull from the elusive twelve animal strong Southern Selkirk herd.

NOTE: Stay tuned for images from our camera traps in the months to come as we return to check them. Follow Kim on instagram at @barefootturtle, David at @moskowitz_david, and the project at #mountaincaribouinitiative for more images from mountain caribou country! Interested in supporting the project? We are still fundraising to cover our research expenses. Tax deductible donations can be made online through project sponsor, Blue Earth Alliance.

Should there be a wolf cull to support Mountain Caribou Recovery? Why We Think there are More Important Questions to be Asking.

written by David Moskowitz, Creative Director Mountain Caribou Initiative has received a number of inquiries about our position on the current wolf “control” activities being carried out in British Columbia in relationship to caribou conservation. This is a subject that has generated a great deal of interest, concern, debate, and strife for a great many people concerned about the plight of both caribou and wolves and the future of the very unique ecosystem in which mountain caribou reside alongside wolves.

Some Background

The relationship between wolves and mountain caribou was actually how I became interested in the story of mountain caribou and the inland temperate rainforest. In my most recent book, Wolves in the Land of Salmon (http://davidmoskowitz.net/publications/wolves-in-the-land-of-salmon/), I spend the better part of a chapter exploring this topic and introducing the reader to the landscape, and the human caused changes to this landscape which have been devastating to both caribou and to the globally unique ecosystem on which they depend. In this chapter I explore the science behind predator-prey dynamics which drive the interactions between wolves and the other large carnivores in this ecosystem and the suite of large prey animals on which they depend which includes primarily moose, deer, elk, and caribou. I carefully review the relationship between human caused changes to the landscape (primarily logging) and changes in the interactions between these predators and prey species.

In Wolves in the Land of Salmon, I carefully lay out how habitat changes from logging and other human impacts have lead to the decline of mountain caribou. Some conservationists believe that the cessation of habitat destruction and the removal of other human stresses to caribou is what we should be doing. Others believe that short-term predator control (killing of native predators in places where they are eating endangered caribou) is required to ensure that the caribou don’t disappear. In the book, I share information from an interview I did with the head of mountain caribou conservation for British Columbia regarding what the province states they are actually doing in this regard.

In the three years since that book was published, this issue has not resolved itself. It has actually become a much more contentious subject. It has fractured what was a very powerful coalition of conservation groups who worked together to promote mountain caribou and forest conservation in the United States and Canada. The province of British Columbia states that they have protected all of the habitat that needs to be set aside for caribou and are carrying out predator control efforts in a precise, targeted, and ethical manner. Some conservation groups and scientists have taken the perspective that this is generally the case. Other researchers and conservation groups have strongly disagreed with this perspective.

Our Stance: If you want us to tell you what to think, you will likely be disappointed.

Our goals with the Mountain Caribou Initiative is NOT to tell people what is right or wrong, what should be done, or should not in regards to predator control, timber extraction, winter recreation, or carbon emissions. We are working to bring our audience our direct observations of what is going on on the ground in this ecosystem. We are working on creating engaging educational content that helps explain what the situation is on the ground right now and how humans have created the problems that caribou and their ecosystem are now facing, as well as shares the responses that humans are having in attempts to address these challenges. In carrying out our research we are working hard to allow the various interest groups involved to share their perspectives. These perspectives will be woven together with a sound foundation of conservation science and culture context to help provide a framework for our audience to interpret these various perspectives.

We believe that the best thing we can do to support the conservation of this animal and its home, is provide our audience with clear, honest, and as unbiased as possible, material so that our audience themselves can come up with their own conclusions about what should be done and help move us in that direction.

Our material will not present the killing of wolves by the province of BC and Alberta as right or wrong. It will explain the various motivations, perspectives and results of these actions that will include the science behind it, as well as the politics, and various perspectives on the ethics of it. I believe the most powerful story and thing for people to understand about the predator control going on related to mountain caribou is about how we got to this point and how the use of such an extreme “conservation” action is being used in conjunction with, or possibly instead of, the long term corrective measures that could ultimately return mountain caribou populations to self-sustaining levels. I don't presume to know what other people should think is right or wrong. I know myself what I think, but my goal here is provide our audience with the opportunity to look into the world of mountain caribou themselves so that they can sort out for themselves what they believe, how they think we should weigh the merits and downsides of various options, and ultimately to understand that this is a story with no neat and tidy answers. We have meddled with this ecosystem, and indeed this entire planet, so much, that every action we take, even with the best of intentions, is fraught with more problems for us to sort out.

Who is our audience?

We are striving to make our material engaging to people from a wide variety of starting points when it comes to thinking about conservation topics: people who love wolves and people who do not, people who know what a mountain caribou is and people who do not, hunters, people who put a roof over their family’s head working in the timber industry, people who build roofs for other family’s heads, people with a home built of wood, environmental studies students, politicians trying to educate themselves about a very challenging subject, powder hounds that wander what sort of animal left the tracks they just skied or snowmobiled over….to name just a few.

I believe that democracy works best when people are educated well and inspired to take responsibility as citizens. It is our goal to provide educational material that will be engaging to many different types of people with many different starting points about what they believe about how the world works and what is right and wrong. After engaging with our resources, it is our goal that our audience will be more informed about the complex ecosystem that caribou live in, the many many ways that humans affect this place, and the options and potential outcomes from various paths forward. And finally, our goal is to translate this knowledge and engagement into actions that will move us towards more aware and responsible use of the fragile resources that we now wield so much power over as a species.

What are our biases?

As I wrote in the introduction to Wolves in the Land of Salmon, "Go See For Yourself", while scientists and reporters who do their job well seek to provide unbiased material, we all carry biases with us that act as the lens through which we see the world and communicate about it. One way that contemporary social scientists address this issue in their research is to state clearly their background and experience so that the person reviewing their research can also understand the perspective from which it was carried out. I have worked intimately with wolves in my work as a biologist, a photographer and as a conservationist working for protections for endangered wolf populations in the United States. As such, I have a great deal of personal connection to wolves in this region, as well as now caribou as my personal experience with this animal has been growing through this current project. Landscapes where large carnivores and other large mammals roam bring an excitement about the world around me that is different then any other experience I have had in my life. Part of my sense of what it means to truly be alive in the world, is to be able to share it with the wide variety of wildlife that have lived along side us humans for millennia...and this is a huge part of my motivation for working on projects such as the Mountain Caribou Initiative.

What are the question that we hope you will be asking:

How can we best move towards conservation stratagies that address whole ecosystems rather than individual species?

How can be best learn from our past mistakes and step up to the daunting challenges of conserving biodiversity in the 21st Century in a multi-faceted and complicated human society?

I hope the story of mountain caribou can act as a case study for us to learn from so that we can approach the many other conservation challenges we are going to face in this century with more foresight, and a higher degree of understanding of the importance of looking at whole systems rather than individual species to create lasting solutions for the problems we have created.

Wildlife and wildland conservation rarely works in the long run if it does not address the needs and concerns of the people who’s lives it affects. We live in diverse human society and because of this we have very different life experiences and cultural references for how we interpret the world. Lasting conservation efforts typically rely on solutions that bring people together rather than divide them. As people interested in seeing biodiversity and ecosystems protected in the years, decades and centuries to come, it is our goal to help be a part of creating conversations that mend wounds, build bridges, and create accountability within our society on local, regional, and global levels.

Editorial Control of our Content

We are grateful for the support of the numerous individuals and organizations that have backed our project in many large and small ways. This collection of people and groups contains a very wide variety of perspectives on the subject we are working on. We appreciate the candid discussions and sharing of experiences, knowledge, and resources we have received from many sources.

As with all of my past projects, we will work diligently to have all of our durable products, such as published articles, photo essays, and video content, reviewed by a wide variety of professionals to ensure the accuracy of the material we present. We however, maintain absolute editorial control over the content and messages we present to our audience, which at times will include material which some of our supporters may take exception to and challenge us on. We welcome your questions and concerns, to help us continue to learn and grow in this journey of discovery and to support the continued use of critical thinking skills which we believe are paramount to success in our efforts to act with reverence and respect for all of our neighbors, and hold ourselves as a society and a species accountable to a higher level of behavior when it comes to how we use the formidable power we have amassed on this planet.

THANKS!

Thanks for taking the time to look at our material. I sincerely hope you see value in the work we are trying to do and will financially support our project and share our work with others. Please let me know if you have any other questions. This is a story that I believe deserves thoughtful answers not soundbites.

Learn more about Mountain Caribou Initiative at davidmoskowitz.net/mci

What is conservation? A View Into the Human Economy in the Heart of Mountain Caribou Country

What is conservation? A View Into the Human Economy in the Heart of Mountain Caribou Country

Revelstoke is a small city in the heart of the Columbia Mountains, about an hour west of Rogers Pass on the Trans Canada Highway. During my recent stay in Revelstoke, British Columbia, the most thoughtful description of the economy was shared with me by Michael Copperthwaite, the General Manager of the Revelstoke Community Forest Corporation. He described it as a resource extraction town with a veneer of ecotourism. A few days in town will confirm that both of these industries have a strong presence in the community. You can watch log trucks, loaded with old growth cedar, roll by to the mill on the south end of town, while stop by one of several excellent coffee shops before your hike, climb, ski, or mountain bike ride. Your helicopter flight to a day of heli-skiing might take you over the hydropower dam on the Columbia River, 5 minutes outside of town. Your day of lift access skiing at the local resort will provide you outstanding views of mountainsides oddly decorated with a patchwork of clearcuts, spreading out in every direction around town. There are two national parks right outside of town, one of which is bisected by the Trans Canada Highway, Canada's most important ground transportation route.

Every inch of this landscape is traditional habitat for mountain caribou. Revelstoke is in the heart of inland temperate rainforest and, as any visitor will tell you, is very, very wet. Caribou here exhibit the double migration pattern typical of the 'mountain' ecotype: spending a chunk of the spring and fall in the valley bottoms, and the summer and winter at high elevations. The two caribou herds in the region are fairing quite differently. The Columbia South herd is heading quickly towards extirpation, with the province listing only 5 animals and having no plans to augment the herd. The Columbia North herd has been the focus of a great deal of attention, and by most estimates its size has “stabilized” with well over 100 animals. The general consensus is that its prospects are better than most.

During 2 weeks in town this winter, I interviewed and/or spent time in the field with folks working in the local timber economy, members of the local Revelstoke Snowmobile Club, and several folks involved in the heli-ski industry. I also met with the Board of Directors for the non-profit Revelstoke Caribou Rearing in the Wild project which is spearheading the experimental program north of Revelstoke to hold pregnant caribou in pens for the period before and after they give birth to protect the cows and calves from predators during the calving season. This project has received the wide support of just about every element of the local community and has served as an opportunity for collaboration and relationship building between various segments of the community who are traditionally at odds with each other.

Daniel Kellie (left), owner of Great Canadian Snowmobile Tours and president of the Revelstoke Snowmobile Club, and club members Ron LaRoy (center), and Brad McStay lean on the front of one of the clubs groomers used to maintain the network of snowmobile trails the club manages all winter. Daniel noted that interest in snowmobiling in the Revelstoke area is growing, adding pressure to the areas currently easily accessible and legally open to to snowmobiling, a number of which have known mountain caribou populations.

Kevin Bollefer, the operations forester for the Revelstoke Community Forest Corporation snowshoeing through one of the stands the corporation has recently harvested in. Kevin and the Community Forest are working on ways to carry out economically viable timber harvest which minimize impacts on caribou. He explained that this is easier to do in locations with high value timber. Locations where the value of the trees is less means that clearcuts are often the only viable option for logging, a result of a combination of market forces and British Columbia’s forest management regime.

Another point that everyone agrees on is that the economy of this community is intimately tied to the natural resources that surround it, from the power of the Columbia River to the deep powder of the numerous mountain ranges. And everyone also understands that, economically, while things are well now, there are problems on the horizon that will need to be reckoned with. As Ian Tomm, Executive Director of the Heli-Cat Canada Association put it, in regards to the heli-ski industry specifically, “Everyone in this industry is pro-conservation. The trouble is in the details of what is conservation.” What is conservation? Each interest group I met with had their own ideas about the problems and potential solutions. Caribou conservation efforts have changed business as usual for everyone in this community, and for the most part everyone is looking forward and attempting to find ways to pro-actively adapt to the changing ecological and business climate.

Over the months to come myself and my collaborators will be returning to the area to collect more material for this story, and to learn more about the ecological interactions between mountains, rainforest, caribou, and humans in this stunning and confusing corner of mountain caribou country.

Mountain Caribou Herds: A Single Organism

Mountain Caribou Herds: A Single Organism

text by Kim Shelton

Recently, I was listening to a podcast by Richard Nelson, a cultural anthropologist who studies human relationships with the natural world. He was recording in the midst of a great caribou migration up in Alaska. As he spoke I could hear the clicking of their hooves and their grunting. His description was so vivid that it felt like I was there in his shoes, being overwhelmed by the smells and the vibration of the earth. He said at one point that observing the caribou made him think that each individual caribou is really just a single cell in a bigger organism. According to Nelson, so much of their existence and identity is wrapped up in being a part of the herd that when one gets separated it's hardly even a caribou anymore.

Mountain Caribou don’t migrate vast distances like the Barren Ground Caribou do, but they are herd animals and they migrate through the elevations, up-and-down, twice a year. Listening to Nelson’s account, I recalled searching for the South Selkirk heard with Dave this summer, a group with only about thirteen individuals at the moment. We were searching for them during the summer so we could get up into the mountains without the snow to impede us. This is also the time of year that Mountain Caribou disperse to avoid predators, so they were extremely difficult to find. As opposed to forming a cohesive unit like they would during the rut in the fall, these few animals were scattered across a patchwork quilt of clearcuts, highways, and intact subalpine forest. They were miles away from each other. Despite their being only thirteen caribou remaining, I wondered why they weren’t travelling together. In a more stable population these Caribou would still be spread out, but would they be completely alone? To a caribou does thirteen even feel like a herd when the comparison is hundreds, even thousands? How big must a herd be to have a gravitational pull on the individual to the whole?

Dave and I were invited to explore the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Darkwoods Conservation Area to search for signs of the South Selkirk herd. Several of the animals in this herd are fitted with GPS collars so wildlife managers can track their movements. Even knowing general locations where a caribou had been recently, in days of searching, we couldn't even find fresh sign of a caribou from the herd, let alone see an actual animal. I thought about how it might feel to be an animal whose entire identity is dependent on the existence of the herd, and to be roaming the land alone. What is a caribou without it’s herd? To me, it meant they were un-findable, invisible, seemingly mythical. It's almost like they're already gone.

I wonder about the South Selkirk Herd's will to survive when they're living life so far from their evolutionary blueprint—in such small numbers at the very southern tip of the caribou universe. How much fight is in them, how much resilience is left as a single cell, disconnected from a greater organism?

This spring we will be headed out on another expedition to Mountain Caribou country, this time further north where populations are larger. Stay posted for updates on how these herds travel together and disperse.

MCP: Cowboy Coffee

Mountain Caribou Project presents: Cowboy Coffee

Everything you ever needed to know about making a really bad cup of coffee in the wilderness....and a little bit about endangered mountain caribou too!

MCP: Of Caribou and Foolish Apes

Guest blog post by Marcus Reynerson; photography by David MoskowitzMarcus Reynerson joined me for a week and a half on the Mountain Caribou Project in the Columbia mountains and Rocky mountains last month. Here are a the first of his reflections from our time in the field.--DM

The end of 88 km of logging roads in the Columbia Mountains. A recent rainforest clearcut.

Humans. Sometimes I find myself so unimpressed. After driving kilometer upon kilometer of BC logging roads though a clear-cut landscape, parts of which were old-growth inland temperate rainforest just 5 years ago, I could not escape my disappointment with Homo sapiens. It boggles my mind to think about how often we accept and value short-term gains at the cost of our long-term future. At the cost of our health, our children’s health, and the health of the planet that gives us life. The more blunt thought that pervaded my travels: “We are just a bunch of dumb apes.”

Marcus Reynerson inspecting a caribou antler he discovered in the old growth forest just uphill from the end of the road and the last clearcut in the valley.

Dave and I were on the trail to find sign – and eventually a live sighting hopefully – of the elusive mountain caribou. Dave was in the field for almost three weeks when I joined him in the Columbia mountains of southern British Columbia. Mountain caribou have developed a survival strategy that is based on being extremely hardy. Basically, they’ve adapted to thrive in environments that are marginal at best for other similar species. Unfortunately, Humans have heavily encroached upon an already hard-pressed landscape. Places ideal for these caribou to call home are dwindling at a precipitous rate. Climate change is taking a strong toll. As the temperature warms, plant communities and ecology are rapidly changing. In some places, the moist cool sub-alpine meadows that have historically supported caribou are disappearing as they become more forested. Overharvesting of timber is creating habitat amenable to deer, elk and moose, which bring predators that are following these ungulates into closer contact with caribou.

Log truck carrying old-growth cedar trees out of caribou country.

It was an incredible tension that I felt cruising the logging roads of British Columbia. For some reason, the province is still harvesting old-growth trees. I found myself incredulous that this was happening still in 2015. The valleys where caribou call home are so beautiful, while at the same time so sad and tragic. Such beauty and devastation all in one place, as far as the eye could see. I’m excited to dig deeper into this story. And I’m also nervous. While it’s a story about the Mountain caribou, it’s also a story about humans. I’m so impressed with the former. At this point I can’t say the same about the latter. More thoughts to come...

When Marcus Reynerson isn't waxing philosophical on the role of humans and caribou in the world, he is the coordinator of the Anake Outdoors School at Wilderness Awareness School in Duvall Washington.

Click here to learn more about the Mountain Caribou Project.

Trees at the edge of a clearcut. Upper Seymour River valley, British Columbia.

MCP: Finding Mountain Caribou in Summer

After 28 days searching for mountain caribou, exploring the places they call home, or have recently disappeared from, here is a summary of some of what I discovered:

Marcus Reynerson making his way across a wet meadow system in the Tonquin Valley, Rocky Mountains. Jasper National Park.

- If you are in mountain caribou habitat, there is a pretty good chance you are either getting harassed by mosquitos, enduring a cold wet summer storm, or both.

Fresh snow on the summit of a peak in the Columbia mountains after a summer storm.

- There are a lot of long logging roads in western Canada and if you are going to find mountain caribou, it will likely be all the way at the end of them, where clear cuts give way to the last stands of uncut forest at the tops of mountain valley and along ridge-lines.

The end of 88 km (55 miles) of logging roads in the Seymour River watershed. Here avalanche chutes mix with recent clearcuts of inland temperate rainforest and remnant patches of old cedar forests where caribou still linger.

- The threats to mountain caribou are varied across their range and even huge national parks and provincial preserves are not necessarily effective by themselves to protect these animals.

The Tonquin Valley, accessible only by trail, and completely contained within Jasper National Park, is home to the largest remaining concentration of caribou in the park but even here caribou numbers are declining rapidly.

- Climate change is here now.The effects of climate change are readily apparent already in many places where mountain caribou live.

Mount Edith Cavell, a famous peak and glacier in Jasper National Park and area still occupied by caribou. Like mountain environments around the globe, the glaciers in the Canadian Rockies and Columbia mountains are retreating quickly. Most of the glaciers I observed while in the field had no accumulation zone anymore, leaving them as large blocks of ice melting in the warming climate.

- Doing nothing is doing something, but perhaps not the something we want to do. Without landscape level conservation measures and ongoing agressive management of caribou and other species of wildlife caribou are ecologically connected to, mountain caribou will likely disappear very soon from much of their current range, as they already have from many places they recently existed. Much of this management is controversial and/or highly invasive to the wildlife and the humans who live, work, and play in caribou habitat including things like culling moose and deer populations, killing entire packs of wolves, landscape scale cessation of logging and or oil and gas mining activity which is the basis of the regional economy, restrictions on winter recreation activities, also an important regional revenue stream.

Moose tracks in the mud in the southern Selkirks. On my first trip to the area in 2009 I found only caribou sign in the area. On this trip all I could find was moose, elk and deer. Burgeoning moose and deer populations across much of the range of mountain caribou have lead to increased predation on caribou from wolves, mountain lions, and other carnivores whose populations are tied to moose and deer.

The survival of mountain caribou is not at all assured across much of their range. In the weeks and months to come I will continue to be researching this topic, planning future trips back to caribou country, collaborating with conservation organizations to help get the word out about this pressing conservation topic. Stay tuned!

MCP: Logging in Mountain Caribou Habitat

A log truck carrying western red cedar logs out of the home range of the Columbia North Caribou herd, past a sign warning motorists to watch out for wildlife on the road.

The timber industry has been the backbone of the economy in most of the interior of British Columbia for several generations. Industrial scale logging is also the primary source of the majority of challenges facing Mountain caribou. Because of this, sorting out how to protect caribou habitat while at the same time dealing with the demands of the very powerful timber industry (and modern civilization for that matter) for lumber has been an especially challenging task in attempts to conserve and restore caribou populations.

How well this has been done varies in different locations around the province. A few thing are clear. Mountain caribou depend on low and middle elevation old growth forests for early winter habitat, and high elevation old growth for winter habitat. Clearcuts and early stages of forest regeneration are prime habitat for moose and deer which attract attention from wolves and mountain lions who then prey on caribou more often in landscapes with a large logging footprint in them. Logging roads become access routes for humans on snowmobile in the winter to areas that are sensitive for caribou who are easily displaced by human recreation activities in the winter. A large amount of habitat has been set aside for mountain caribou which has curtailed logging in some areas and road use restrictions have been put in place as well. However, logging of both old growth and second growth forests continue in mountain caribou habitat in some places.

Lumber yard in Revelstoke, British Columbia. The logging industry is a primary employer in much of the region.

Mill worker on his way to work at the lumber mill in Revelstoke, British Columbia, a town where both timber and tourism are major and at times competing components of the economy. Mountain caribou conservation has put stresses on both in terms of restrictions on logging as well as the heliski and snowmobile recreation which are big business in the area.

British Columbia is the last place in the Pacific Northwest with significant stands of old growth forest still slatted for logging, both on the coast and in the interior. Conservation groups have used caribou protection as a tool to curtail logging in these ancient forests, much the spotted owl was used in the United States several decades ago—imperfectly in both cases. With caribou populations continueing to decline in much of their range logging interests have started looking at having these restrictions lifted once the caribou disappear from an area while conservation groups are looking at what might be the next lever for protecting whats left of this unique inland temperate rainforest.

A recently logged second growth forest in the Seymour River watershed. Industrial scale logging which employs large machinery to cut and remove logs often leaves a devastated appearing landscape behind, including lots of wood cut and left on the ground, to expensive to transport out for the value of what can be made from it.

The likely destination of the logs cut in the landscape above. Stacked lumber with floating logs beyond them close to Salmon Arm, British Columbia

Kim Shelton takes in the grandeur of a remnant stand of old growth western red cedar close to Trout Lake British Columbia. How we as a society place value on forests and trees such as these is highly varied. Whether places such as this, and the animals such as mountain caribou whom depend on them, will continue to exist in any significant quantity for future generations to argue about seems tenuous at the moment.